Maya Deren - Meshes of the Afternoon

Man Ray

Richard Avedon

Diane Arbus

Andrei Tarkovsky

Robert Mapplethorpe

Explorando el mundo del documental

Background notes:

**You will hear some New Guineans speaking a language called Tok Pisin, a language originally developed as pidgin language, but now a fully developed creole language.

**According to http://www.oanda.com/convert/classic, in Jan. 1996, 1 kina was equivalent to $0.755 U.S. dollars.

**According to http://www.encyclopedia.com/html/section/papuanew_history.asp: "Papua, the southern section of the country, was annexed by Queensland [Australia] in 1883 and the following year became a British protectorate called British New Guinea. It passed to Australia in 1905 as the Territory of Papua. The northern section of the country formed part of German New Guinea from 1884 to 1914 and was called Kaiser-Wilhelmsland. Occupied by Australian forces during World War I, it was mandated to Australia by the League of Nations in 1920 and became known as the Territory of New Guinea. Australian rule was reconfirmed by the United Nations in 1947. In 1949 the territories of Papua and New Guinea were merged administratively, but they remained constitutionally distinct. They were combined in 1973 as the self-governing country of Papua New Guinea. Full independence was gained in 1975."

**First village in film: Kanganaman.

**PNG was a German colony under Kaiser Wilhelm II. The colonies were lost in WWI.

Frases clave del film:

"Those were good times with the Germans, right? That what I have heard about Africa, too." - Turista Alemán

Tres Italianos platicando “primitive people”: “really living with nature.” “In a way, hey don’t really live. It's more like vegetating in their environment.” “But maybe their life is better than ours---truly living with nature.” “They don’t seem sad.” “No, they are satisfied....They are delighted.” “They don’t have to worry about tomorrow.”

Los de Nueva Guinea les llaman a los europeos: “The dead have returned.”

New Guinean man: “We say they must be wealthy people. Their own ancestors made money.” “We don’t have money, so we stay in the village. If not I might go on the ship with them.”

New Guinean man: “Tourists read about us in books. They come to find out if we live like our ancestors.” He admits he doesn’t understand why they come. “I’m confused.”

Cameraman asks a New Guinean man: “Why do you allow tourists to come here?” Answer: “Because we get money.”

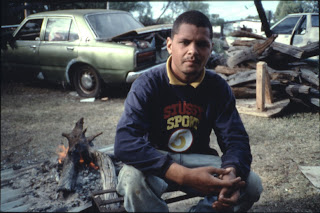

Younger New Guinean man: “We are friendly towards them. We don’t understand why these foreigners take photographs.” While he is talking to the cameraman, a woman sneaks up behind him and takes his photo. He is handed a coin. The cameraman says, "It's hard to make a dollar." Answer: "Yes."

Older man: “We must try to stimulate certain desires, so that they see things from our point-of-view—and also our clothes, the way we dress as tourists....They need to be helped.” “The problem is apathy and indolence, living in a world completely overwhelmed by nature.” “We have the good fortune to be born into a more evolved society.”

Análisis del film:

¿Quién es Dennis O'Rourke dentro del film? Un colonizador más. Es evidente que los turistas funcionan como conlonizadores de los Papua. Pero, ¿O'Rourke a quién coloniza? Coloniza a los colonizadores. Y lo hace de una manera brillante: Les hace creer que es uno de ellos, un colonizador más de los Papua. De esta manera logra obtener su confianza y acercarse a ellos para así lograr a su vez hacerles un examen antropológico. Los europeos responden a las preguntas abiertamente creyendo que están ayudando a O'Rourke a saber más de los Papua, sin darse cuenta de que lo que el director en realidad está analizando es la relación que se genera entre ambas culturas, y que al ellos formar parte esencial de esta relación, son objeto de estudio también. Los Papua montan un show para los europeos, pero los europeos a su vez montan un show para la cámara, porque todo el mundo monta un show para la cámara. Es imposible no ser colonizado por una cámara, no entrar en su juego estando consciente de la presencia de ésta. La cámara lo cambia todo. Sin embargo la relación Papua-cámara y europeos-cámara es completamente distinta. Los primeros lo usan como un medio de expresión, para quejarse de la dominación de la cultura occidental, y la manera en la que su actitud cambia ante la cámara es más sutil debido a que lo primordial para ellos son los europeos. A los papua no les importa quedar mal ante la cámara porque carecen de imagen propia, su imagen la venden a diario a Occidente, no creen poder denigrarse más y por esto pareciera que son inmunes a la colonización de la cámara. Del otro lado están los europeos que intentan impresionar a la cámara con su cultura, con su apertura y sus pensamientos colonizadores. Sonríen, usan su mejor ángulo, desempolvan palabras domingueras e ideas alguna vez leídas en libros cultos, caen en el juego de la cámara y montan un show para ella. Cuando otro occidental resulta ser el espectador y la mira no puede evitar verse reflejado y al verlo desde afuera, sabiendo que por su soberbia no logran darse cuenta de que ellos también son parte del espectáculo generan pena-ajena.

"La diferencia entre los franceses y los españoles es que ellos no saben nada de nosotros y nosotros sabemos todo de ellos."

- Luis Buñuel

%2520copy.jpg)

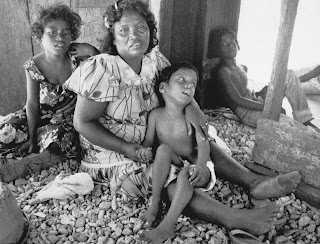

"Dead Birds is a film about the Dani, a people dwelling in the Grand Valley of the Baliem high in the mountains of West Papua. When I shot the film in 1961, the Dani had a classic Neolithic culture. They were exceptional in the way they dedicated themselves to an elaborate system of ritual warfare. Neighboring groups, separated by uncultivated strips of no man's land, engaged in frequent battles. When a warrior was killed in battle or died from a wound and even when a woman or a child lost their life in an enemy raid, the victors celebrated and the victims mourned. Because each death needed to be avenged, the balance was continually adjusted by taking life. There was no thought of wars ever ending, unless it rained or became dark. Wars were the best way they knew to keep a terrible harmony in a life that would be, without them, much drearier and unimaginable.

Dead Birds has a meaning that is both immediate and allegorical. In the Dani language the words refer to the weapons and ornaments recovered in battle. Their other more poetic meaning comes from the Dani belief that people, because they are like birds, must die.

Dead Birds was an attempt to film a people from within and to see, when the chosen fragments were assembled, if they could speak not only about the Dani but also about ourselves."

-Robert Gardner

-Robert Gardner

Studio7Arts is resolutely non-profit in its approach to the market but it will not repudiate the possibility of gain from its undertakings, as long as its principles are not violated. It is heavily committed to the production of films, videos, DVDs, books and other publications having a variety of aims and intentions. To date, expenses are met by contributions and grants.

Arriba Nicolás Echevarría con María Sabina. Tema principal de su primer largometraje: María Sabina. Mujer Espíritu. Documental en el que la presenta “natural y en plena libertad de movimiento que nunca posa para la cámara, simplemente se muestra, interactúa, conversa en su lengua nativa y acomete sus ceremonias mágicas” .

Arriba Nicolás Echevarría con María Sabina. Tema principal de su primer largometraje: María Sabina. Mujer Espíritu. Documental en el que la presenta “natural y en plena libertad de movimiento que nunca posa para la cámara, simplemente se muestra, interactúa, conversa en su lengua nativa y acomete sus ceremonias mágicas” . "¿Qué pensará Carlos Castaneda de la inmensa popularidad de sus obras? Probablemente se encogerá de hombros: un equívoco más en una obra que desde su aparición provoca el desconcierto y la incertidumbre. En la revista Time se publicó hace unos meses una extensa entrevista con Castaneda. Confieso que el "misterio Castaneda" me interesa menos que su obra. El secreto de su origen -¿es peruano, brasileño o chicano?- me parece un enigma mediocre, sobre todo si se piensa en los enigmas que nos proponen sus libros. El primero de esos enigmas se refiere a su naturaleza: ¿antropología o ficción literaria? Se dirá que mi pregunta es ociosa: documento antropológico o ficción, el significado de la obra es el mismo. La ficción literaria es ya un documento etnográfico y el documento, como sus críticos más encarnizados lo reconocen, posee indudable valor literario. El ejemplo de Tristes Tropiques -autobiografía de un antropólogo y testimonio etnográfico- contesta la pregunta. ¿La contesta realmente? Si los libros de Castaneda son una obra de ficción literaria, lo son de una manera muy extraña: su tema es la derrota de la antropología y la victoria de la magia; si son obras de antropología, su tema no puede ser lo menos: la venganza del "objeto" antropológico (un brujo) sobre el antropólogo hasta convertirlo en un hechicero. Antiantropología.

"¿Qué pensará Carlos Castaneda de la inmensa popularidad de sus obras? Probablemente se encogerá de hombros: un equívoco más en una obra que desde su aparición provoca el desconcierto y la incertidumbre. En la revista Time se publicó hace unos meses una extensa entrevista con Castaneda. Confieso que el "misterio Castaneda" me interesa menos que su obra. El secreto de su origen -¿es peruano, brasileño o chicano?- me parece un enigma mediocre, sobre todo si se piensa en los enigmas que nos proponen sus libros. El primero de esos enigmas se refiere a su naturaleza: ¿antropología o ficción literaria? Se dirá que mi pregunta es ociosa: documento antropológico o ficción, el significado de la obra es el mismo. La ficción literaria es ya un documento etnográfico y el documento, como sus críticos más encarnizados lo reconocen, posee indudable valor literario. El ejemplo de Tristes Tropiques -autobiografía de un antropólogo y testimonio etnográfico- contesta la pregunta. ¿La contesta realmente? Si los libros de Castaneda son una obra de ficción literaria, lo son de una manera muy extraña: su tema es la derrota de la antropología y la victoria de la magia; si son obras de antropología, su tema no puede ser lo menos: la venganza del "objeto" antropológico (un brujo) sobre el antropólogo hasta convertirlo en un hechicero. Antiantropología. La desconfianza de muchos antropólogos ante los libros de Castaneda no se debe sólo a los celos profesionales o a la miopía del especialista. Es natural la reserva frente a una obra que comienza como un trabajo de etnografía (las plantas alucinógenas -peyote, hongos y datura- en las prácticas y rituales de la hechicería yaqui) y que a las pocas páginas se transforma en la historia de una conversión. Cambio de posición: el "objeto" del estudio -don Juan, chamán yaqui- se convierte en el sujeto que estudia y el sujeto -Carlos Castaneda, antropólogo- se vuelve el objeto de estudio y experimentación. No sólo cambia la posición de los elementos de la relación sino que también ella cambia. La dualidad sujeto/objeto -el sujeto que conoce y el objeto por conocer- se desvanece y en su lugar aparece la de maestro/neófito. La relación de orden científico se transforma en una de orden mágico-religioso. En la relación inicial, el antropólogo quiere conocer al otro; en la segunda, el neófito quiere convertirse en otro.

La conversión es doble: la del antropólogo en brujo y la de la antropología en otro conocimiento. Como relato de su conversión, los libros de Castaneda colindan en un extremo con la etnografía y en otro con la fenomenología, más que de la religión, de la experiencia que he llamado de la otredad. Esta experiencia se expresa en la magia, la religión y la poesía pero no sólo en ellas: desde el paleolítico hasta nuestros días es parte central de la vida de hombres y mujeres. Es una experiencia constitutiva del hombre, como el trabajo y el lenguaje. Abarca del juego infantil al encuentro erótico y del saberse solo en el mundo a sentirse parte del mundo. Es un desprendimiento del yo que somos (o creemos ser) hacia el otro que también somos y que siempre es distinto de nosotros. Desprendimiento: aparición: Experiencia de la extrañeza que es ser hombres. Como destrucción critica de la antropología, la obra de Castaneda roza las opuestas fronteras de la filosofía y la religión. Las de la filosofía porque nos propone, después de una crítica radical de la realidad, otro conocimiento, no-científico y alógico; las de la religión porque ese conocimiento exige un cambio de naturaleza en el iniciado: una conversión. El otro conocimiento abre las puertas de la otra realidad a condición de que el neófito se vuelva otro. La ambigüedad de los significados se despliega en el centro de la experiencia de Castaneda. Sus libros son la crónica de una conversión, el relate de un despertar espiritual y, al mismo tiempo, son el redescubrimiento y la defensa de un saber despreciado por Occidente y la ciencia contemporánea. El tema del saber está ligado al del poder y ambos al de la metamorfosis: el hombre que sabe (el brujo) es el hombre de poder (el guerrero) y ambos, saber y poder, son las llaves del cambio. El brujo puede ver la otra realidad porque la ve con otros ojos -con los ojos del otro."

-Octavio Paz.