"In a ideal world, I would be able to refuse to discuss the form or the style of my films; it is inevitable that any explanations I give will be arrogant and pedantic. I am aware that what I believe I am doing is not necessarily what others will think. Each film is the result of the accretion of millions of tiny details - in image and sound and movement and text - and every one of these details can be the subject of interpretation. Also, in my ideal world I would never have to elaborate on the content of my films or their sources of inspiration because the films contain enough of what I want to say and what I believe (but not necessarily what is 'true'). The rest can only really be gossip and speculation.

I believe that documentary films should not exist outside of the reality, which they attempt to depict. The magic of the documentary film is that one can start to create with no idea of the direction of the narrative and concentrate all thinking on the present moment and thing. It is important, when you make a film, not to be rational but instead to trust your emotions and intuition. In fact, you have to be irrational, because when you try to be rational the true meaning and the beauty of any idea will escape you.

I think the story is much less important than the ideas and the emotions, which surround it. I try to give you my idea of a palpable 'truth', but which is presented comfortably, imperceptibly, as an illusion. I try to concentrate on the small, intimate details; using reduction and understatement. I like to think that, in my films, nothing really happens but it happens very quickly.

I think the story is much less important than the ideas and the emotions, which surround it. I try to give you my idea of a palpable 'truth', but which is presented comfortably, imperceptibly, as an illusion. I try to concentrate on the small, intimate details; using reduction and understatement. I like to think that, in my films, nothing really happens but it happens very quickly.

%2520copy.jpg)

All this is made possible by those beautiful recording angels - cameras and tape recorders - who watch and listen for me while I stumble, trance-like, through the field of ideas. Like the ideal tourist, I travel on a journey of discovery - on an unmarked road, to see where it leads. And I travel not in order to return; I cannot return to the point-of-departure because, in the meantime, I have been changed. This is why I say: “I don't make the film, the film makes me.”

I make documentary films (as opposed to fiction films) not because I think they are closer to the truth, but because I am convinced that, within a reinvented form of the non-fiction film, there is a possibility of creating something of very great value - a kind of cinema-of-ideas, which can affect the audience in a way that no Hollywood-style theatrical entertainment films can. I make documentary films because I believe in a cinema, which serves to reveal, celebrate and enlighten the condition of the human spirit and not to trivialise or abase it. I don't do it to provide information to people; I do it to touch people and to provoke and astound them, and to make the truth that we already know more real to us.

"I believe it is critical that both film makers and film viewers be rid of the fantasy that a documentary film can be some kind of pure and un-problematic representation of reality, and that its 'truth' can be conveniently dispensed and received, like a pill to cure a headache. So in my film work of recent years I have sought to resist and repudiate the lure of that self-gratification which comes from making earnest statements-to-the-converted. These days, I feel more rewarded when certain sanctimonious critics are upset or outraged by my films, rather than when they smugly praise them. "

-Dennis O'Rourke

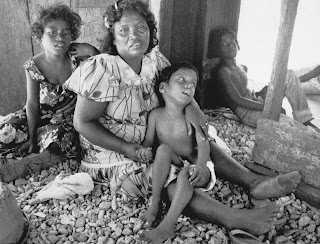

"CANNIBAL TOURS" is two journeys. The first is that depicted - rich and bourgeois tourists on a luxury-cruise up the mysterious Sepik River, in the jungles of Papua New Guinea ... the packaged version of a 'heart of darkness'. The second journey (the real text of the film) is a metaphysical one. It is an attempt to discover the place of 'the Other' in the popular imagination. It affords a glimpse at the real (mostly unconsidered or misunderstood) reasons why 'civilised' people wish to encounter the 'primitive'. The situation is that shifting terminus of civilisation, where modern mass-culture grates and pushes against those original, essential aspects of humanity; and where much of what passes for values in western culture is exposed in stark relief as banal and fake.

“CANNIBAL TOURS” is certainly a documentary film but it is also a fiction because it is an artefact, that is: someone made it. The making of art is, after all, only artifice - playing with the undifferentiated mess of life to get a little product. But this can be both the meaning and the subject matter. In a profound sense the viewer and the subject can be one-and-the-same. We can be embarrassed to be inside and outside the frame (and the process of film making), simultaneously. This experience of self-recognition and embarrassment is the subject matter.

In “CANNIBAL TOURS” we can recognise in these Western tourists both the hopelessness of their experience and we can recognise ourselves. We can also recognise (at least sub-consciously) the tourists’ implicit understanding that anyone who will see them in the film shares their sense of hopelessness, in the face of such a futile search for utopian meaning, which is their tourist experience.

I can only touch on some of the ideas that influenced me during the making of the film and I will confine my remarks to tourism in traditional societies, because this is where I have some experience. However, I can imagine that what applies in Papua New Guinea does also apply in many other places in the Pacific and around the world, including even, some which are in the developed world.

I make documentary films (as opposed to fiction films) not because I think they are closer to the truth, but because I am convinced that, within a reinvented form of the non-fiction film, there is a possibility of creating something of very great value - a kind of cinema-of-ideas, which can affect the audience in a way that no Hollywood-style theatrical entertainment films can. I make documentary films because I believe in a cinema, which serves to reveal, celebrate and enlighten the condition of the human spirit and not to trivialise or abase it. I don't do it to provide information to people; I do it to touch people and to provoke and astound them, and to make the truth that we already know more real to us.

"I believe it is critical that both film makers and film viewers be rid of the fantasy that a documentary film can be some kind of pure and un-problematic representation of reality, and that its 'truth' can be conveniently dispensed and received, like a pill to cure a headache. So in my film work of recent years I have sought to resist and repudiate the lure of that self-gratification which comes from making earnest statements-to-the-converted. These days, I feel more rewarded when certain sanctimonious critics are upset or outraged by my films, rather than when they smugly praise them. "

let me quote one line from the very beautiful Psalm 90. I would often read this psalm in the copy of the Gideon's Bible which was in my room in the squalid Rose Hotel. Not all versions have this translation (and perhaps there is a bit of my own poetic licence here too). The words are:

"We live our lives as a tale that is told."-Dennis O'Rourke

"CANNIBAL TOURS" is two journeys. The first is that depicted - rich and bourgeois tourists on a luxury-cruise up the mysterious Sepik River, in the jungles of Papua New Guinea ... the packaged version of a 'heart of darkness'. The second journey (the real text of the film) is a metaphysical one. It is an attempt to discover the place of 'the Other' in the popular imagination. It affords a glimpse at the real (mostly unconsidered or misunderstood) reasons why 'civilised' people wish to encounter the 'primitive'. The situation is that shifting terminus of civilisation, where modern mass-culture grates and pushes against those original, essential aspects of humanity; and where much of what passes for values in western culture is exposed in stark relief as banal and fake.

“CANNIBAL TOURS” is certainly a documentary film but it is also a fiction because it is an artefact, that is: someone made it. The making of art is, after all, only artifice - playing with the undifferentiated mess of life to get a little product. But this can be both the meaning and the subject matter. In a profound sense the viewer and the subject can be one-and-the-same. We can be embarrassed to be inside and outside the frame (and the process of film making), simultaneously. This experience of self-recognition and embarrassment is the subject matter.

In “CANNIBAL TOURS” we can recognise in these Western tourists both the hopelessness of their experience and we can recognise ourselves. We can also recognise (at least sub-consciously) the tourists’ implicit understanding that anyone who will see them in the film shares their sense of hopelessness, in the face of such a futile search for utopian meaning, which is their tourist experience.

I can only touch on some of the ideas that influenced me during the making of the film and I will confine my remarks to tourism in traditional societies, because this is where I have some experience. However, I can imagine that what applies in Papua New Guinea does also apply in many other places in the Pacific and around the world, including even, some which are in the developed world.

los artículos y entrevistas completos se encuentran en el link de abajo:

http://www.cameraworklimited.com/articles.html

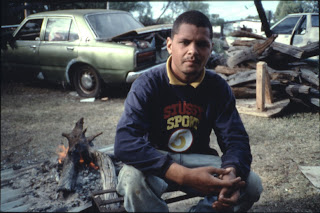

*Todas las fotos son creación de O'Rourke, menos la primera en la que sale él y que tomó Mark Rogers en el 2005.

FUENTES:

- Camera Work: Films about the Real. Cannibal Tours. http://www.cameraworklimited.com/films/cannibal-tours.html

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario