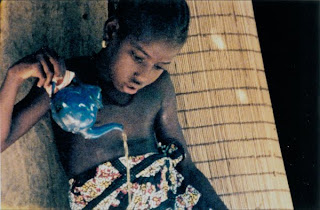

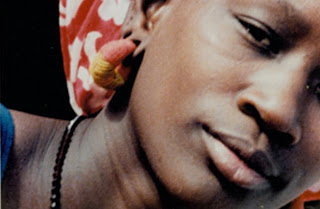

In her first film, Reassemblage (1982), she explores how she can avoid a top-down perspective on the Senegalese women who are the main subject of the film. Trinh does not want to be an objective outsider explaining to the viewer how the Senegalese women spend their daily lives. She wants to get closer, but at the same time she realises that she is different and cannot be one of them. Trinh reflects on these concerns in the film, thus turning it into a source for alternative ideas for ethnographically inspired documentary filmmaking. One of these ideas is to focus on the perception of reality and not reality itself, for instance by including reflections on the film medium in the film itself.

In Reassemblage she explores different methods to reflect. What it means to take a perspective is one of them. MacDonald phrases this accurately in an interview with Trinh about her film: “The subject always stays in its world and you try to figure out what your relationship to it is. It’s exactly the opposite of “taking a position”: it’s seeing what different positions reveal”. [Trinh, T. Minh-ha (1992). Framer Framed, Routledge.] By not taking a fixed or preferred position herself in her film, Trinh does not allow the viewer to comfortably follow her. Every viewer has to put effort in her/his own exploration of different ways of seeing the people in the film. The aim of Trinh to “just speak nearby” results in a multitude of stories and perspectives. Each viewer can create her/his own relationships to these.

Trinh does not only bring her many perspectives into the film; Reassemblage sets up a conversation between its viewers, the filmmaker and the people in the film. The techniques that Trinh has chosen to do this do not make it very easy to watch because the film is despite its constructed nature fragmented, and it requires work to bring these fragments together. Trinh leaves it for a large part up to the viewer to create a synthesis from the observations and reflections she offers, unlike for instance Ivens who in for instance Rain offers a clear synthesis of his observations and the perspectives he developed to the spectator.

Trinh T. Minh-Ha says that she set out to make Reassemblage as an ethnographic film that paid no heed to conventions of documentary. It seems from interviews with her that her attempt wasn’t exactly to “defy” convention as to ignore it. This certainly seems questionable, just like her assertion that she hasn’t been influenced by any experimental films (which she contradicted in the same interview by saying she is unable to count her numerous influences). But to be fair, she isn’t overly concerned with classical Western notions of “consistency” and “contradiction,” rather more inclined to embrace dissonances in Eastern (or even Nietzschean) form while holding to a slightly more optimistic (albeit equally problematic) ideology.

Regardless of her thoughts on her own un/conscious, Reassemblage is a remarkable film for seemingly achieving what it set out to do: break with documentary and ethnographic tradition by questioning the positions of the filmmaker and audience in relation to the film’s subject(s). The highly poetic voiceover dialogue within the film states that she wanted to make a film “on Senegal,” to which her friends replied, what about Senegal? The lack of answer to this question functions well with the exploratory nature of the project. Apparently her only plan in making the film was to travel to five different regions of Senegal and record what she saw. She self-consciously proclaims her own presence through word and camera, though she is never actually seen on screen. The feminist nature of the film acts as a further acknowledgement of her presence and positioning: if the film has any “subjects,” they are the women of these regions of Senegal. Previous and conventional ethnographies, which have tended to be made by white men, have focused on the doings of males in third-world countries and only seen women as objects of exotic voyeuristic value. Trinh, however, switches the focus onto women while still cinematographically acknowledging the fetishistic male gaze of “native” women in all their unclothed glory. Her extreme close-ups, then, ironically cater to the male viewer’s expectation while simultaneously critiquing it. If the male viewer treats women like objects, Trinh has reversed the formula, turning objects back into women.

FUENTES:

- Reassamblage (Senegal, 1982) Trinh Minh-ha. by Moviola. http://www.flickr.com/photos/documentaries/171380206/

- Precious Bodily Fluids. Reassamblage. 13 nov 08. http://andrewsidea.wordpress.com/2008/11/13/reassemblage/

- Trinh T. Minh-ha. http://www.trinhminh-ha.com/

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario